Games are, in their core, fun, entertaining experiences. But they can also be so much more! ‘Serious games’ (not a fan of this term) can be used for education, exercise, mental health, and even advertising and propaganda. I’ve also recently come across the idea of game poems, a term discussed in my earlier interview with Jordan Magnuson..

This time, I talked to Kaitlin Bonfiglio, known online as KB. She is a game designer, sex educator, and researcher whose work lives at the crossroads of care, creativity, and community. Also a writer who has created both prose and poetry, she brings an emotional depth and literary sensitivity to her interactive works, whether it’s a Twine experiment or an award-winning educational game.

She currently teaches at the University of Southern California and explores how participatory design can be used to support community health and sex education. Her game (val)iant, which won the Games for Change "Best Student Game" award, addresses chronic pelvic pain.

I spoke with KB about her approach to design, her inspirations, and how her work invites us to feel, reflect, and maybe even cry a little.

👻 Your work blends design, education, poetry, and advocacy. How did you find your voice as a creator across all these spaces, and how do you decide when an idea becomes a game, a poem, or something in between?

There's so much there to answer! I will say that I do come from a literature and language background: my undergrad degree is in English. So I started writing traditional poetry — and by that I mean not interactive, or you know, digital computational media.

I worked as a middle and high school teacher. And I had always loved games, and specifically digital games. And I was like, "You know... I kind of like coding. I'm not very good at it, I don't know a lot about it, but I would love to go back to school to do this for real".

And this was a huge deal because it was a total career shift from being in education in the primary, secondary level. Getting my MFA in game design was a huge shift.

But it turns out there are — like you and I — a lot of people who make educational games. I have so many thoughts about what is an educational game, the purpose and value of games for learning and games for education. But yeah, that's just my general background.

Now, thinking about my creative practice, ideas and all that fun stuff...

Let me just interject and say, the interview you published with Brendan Allen... I loved that, especially when he talked about the constraints of poetry and game design.

And it's so obvious to me now, but I didn't really think about it until I had read it in this interview! I was like, "Oh, that that is so true". It makes perfect sense. I think there is a lot of overlap between poetry and games.

And that's why I was so excited to see that Jordan had created this community of game poets.

I have ADHD and I've always struggled to focus on creative projects for a very long time. And that's why I think poetry immediately spoke to me, because I would just get the lightning of inspiration and start writing!

Ideas would come to me, and on a good day, I'd be sitting down at my computer, which is where I usually write, and just let it out.

Of course, like any creative person, there's a lot of times where it's more sudden. I think it was Sherman Alexie who said: "More dangerous than texting and driving is writing poems and driving", as in, you're driving along and then you're like, "Oh, this would be such a good idea for a poem".

So poems are great because you can really bring that idea to life in a small and constrained, but still very impactful and emotional way. And I just love it, God, there's so much I can talk about with poetry and language. I could just go on and on.

Of course, not all poems are short. But the poems that I've always loved are very much like bursts of emotion, I think. Maybe because I felt that way too.

There's a writer named Hanif Abdurraqib who said that people don't usually turn to poetry in times of joy. Many times, it's sadness that brings people to it. And I related to that so strongly, because I would have these really intense feelings, and writing poetry was my way to channel that.

And in this era, there are so many cool, digital, interactive, poetic ways of creating. And I think games and game poems are a perfect example of that.

As I was completing my degree in game design and learning about the process of making a game, ideating it and prototyping, a similar thing would happen, in relation to writing poetry.

You're studying this stuff, and suddenly you're like "Hey, this would be a great idea to try out, maybe I should create a prototype of sorts".

I will say that a difference for me personally though is — as someone who's not a very strong programmer — it wasn't quite as easy as just writing something down.

You really have to be intentional about it. If you have an idea for something, like "what if when I move the mouse, this happens?", bringing that to life takes a long time as opposed to just writing a couple lines.

I'm not trying to say that poetry is easy to write, but I would say that the creative process is slightly different, because the actual creation of an interactive project is more time consuming compared to a poem.

When I'm writing, I go "Oh, yeah". And then I'm like, "No, there's a better way to say that". And you know, you come back to the piece the day after or multiple days later and say, "Oh, no, I would have said it like this". But the total process can take, I don't know, a matter of hours, all together, and then you could have something that exists.

But then, these days, creating interactive media has also gotten easier. In your interview, Brendan also mentioned Anna Anthropy's “Rise of the Video Game Zinesters” and I love that book. In the book — which was written almost 15 years ago at this point — she mentions the rise of these new tools that are being used by everyday people. People who would not define themselves as programmers, but that are still creative and want to make games and interactive media.

So there's Twine. There's now Bitsy, which is a big foundation of the game poets' Discord server. There's a lot of no code tools. There's just basic HTML and CSS that people also use.

So I think creating these experiences is becoming more popular, especially after that book was published, which is really, really exciting to see! The gatekeeping walls of game development are coming down, I think.

And Anthropy knew this was happening, because it was happening when she wrote it. And now, 13 years later, it's really exciting to see so many people on itch.io, so many people using Bitsy, and so many people making Twine games.

So what I am trying to say is that nowadays, you could make a game in a matter of hours, which feels kind of insane! If you think about traditional game development, games take so long to make for a variety of reasons. And now, with these tools, it's so much easier.

👻 Let’s talk about (val)iant). I loved it, really. I'm a sucker for nice art, so the fact that it is a gorgeous game played a part, but the mechanics are also incredible. Right from the start, like when you are playing an impossible version of Tetris during a difficult conversation with a Medical Doctor. So the mechanics are very intertwined with the narrative, and they are telling the story too; it reminded me of Florence.

Florence is a good reference, because it is a game that was a big inspiration for us.

👻 And that may be a hot take, but especially in the area of serious games, I feel like so many of them have the game mechanics, the narrative and the learning goals as completely disconnected entities.

Yeah!

👻 But anyway! Back to (val)iant): you worked as its creative director. And it's a super powerful, highly narrative educational piece; kudos to the team, by the way, the end result was amazing! What was it like to design a game around such a specific theme — chronic pelvic pain — and how did you approach the balance between vulnerability and accessibility?

First of all, thank you for playing (val)iant), and I will pass along your note about the art. I love my art team: they did a fantastic job. My whole team is incredible!

People don't usually describe (val)iant) as fun. They usually describe it as powerful, and also say things like "I hated that I couldn't play this minigame right". Especially the rhythm game where Val's talking to their partner at the time.

As you know, those minigames are impossible and very frustrating to play, and that was kind of the whole point.

So, the impetus for making this game, and the reason for me being its creative director, is that it is my thesis from USC Games! We spent the whole last year of my graduate studies making that game.

I have always been really big on stories and storytelling. I love literature and language, but I didn't really know a lot about narrative medicine. When I started making this game, I didn't really consider myself a person with a patient narrative or a person with a public narrative.

I just wanted to talk about my experiences with this specific thing: chronic pelvic pain. I have something called pelvic floor dysfunction, and a lot of people have this too! It's actually very common, but it's just not very talked about in the world, and especially not in the United States, where I'm born and raised.

So my game is an interactive story of my own experiences. Of course, the character Val is not me: it's a semi-autobiographical game. But it is largely based on my experiences, in the doctor's office, talking to my friends, talking to my parents, talking to my partners, about the fact that something's wrong with me, like, "I can't have sex".

That is one of the ways in which people find out they have pelvic pain. But pelvic pain also includes pain on your period, endometriosis, pain wearing certain clothing, or if there's something up with your urinary frequency, such as if you're peeing all the time; that's all pelvic pain.

There's a lot of different ways that bring people into this specific world. Mine was that I seemed to be mostly normal — whatever that means — in my day to day life, but it was when I first started becoming sexually active that I realised that I was like: "This thing that everyone says they can do... and that it's maybe a little scary at first, but mostly very fun and cool and pleasurable... I cannot do it".

And I was so ashamed and shocked... and thinking, "this is supposed to be a rite of passage for human beings, losing your virginity and all that".

And I also grew up in a complicated landscape because I went to a Catholic school, which you can see in Val's experiences.

In their middle school, there's a scene with a teacher who's talking about abortions and how people shouldn't get them, and that's directly based on my own experiences at that Catholic school.

But I also grew up with a lot of sexualised media everywhere. And there was an idea of "if you're not having sex, then you're a prude and you're not a real feminist". And that just didn't align with who I was as a person. I thought of myself very much as a feminist, and I was like, "does this mean something about me, the fact that I can't do this, or that I don't want to do this because it hurts so much"?

It was just a very complicated, confusing situation that I think can partially be explained by the fact that this kind of chronic pelvic pain is something that many people just don't talk about, but millions of people have. But no one wants to talk about how it's not fun to have sex, right?

So I wanted to talk about this, and a way that I could talk about it was by making a video game about this topic. You know, I could have written an essay, and I have written many poems about my experiences. But I was making a thesis for my graduate school, and once the idea was planted in my head, I wasn't going to do anything else.

As kind of a little side note, the conversation that led to me doing this game was like a joke. I was like, "Oh, it would be so funny to make a game about my broken vagina". And then I was like, "Wait, that's actually not a bad idea". And that conversation led to part of the title of the game being Val's Guide to Having a Broken Vag.

After I said that, I felt that maybe I was onto something. Games are a really interesting way to tell a story, playing with the concept of fun and immersion.

And as I was creating the game, it was a pretty collaborative experience; I had a team making it with me! I had to keep having these conversations with them, over and over again: "what is pelvic pain"? And they would respond. "Wait, I might have that". "Wait, I think I dated someone who had that".

And once you open the can of worms that is sexuality, everything comes out. I just had a vision of opening a can of worms, but they are actually like butterflies. There are so many things we can talk about when it comes to sexuality.

I think one of my favourite parts of making (val)iant) is that I had those conversations over and over and over again with people. I was not sure that anyone would want to work on this game with me. I thought I was going to be doing it alone.

I ended up having like 15 people.

👻 Yeah, it's quite a big team!

Yeah. There were core people who were doing a lot of work over the course of nine months. And then there were people who helped out here and there. And (val)iant) is only able to exist because of all of those people. And every one of them had their story to tell as far as sexuality and reproductive health goes.

So it was scary for sure. It was like "Oh God, I have to talk to my professor about the clitoris", you know, I was like, "I don't know how this is going to go". And there were a lot of bumpy moments, but that's how sex education is.

And, especially in America, we are so... reticent isn't even the right word, because it's more than that. It's like there's a wall, we do not want to have those difficult conversations, but we have to.

Particularly if you're considering pleasure-based sex ed, not just the whole "put on a condom and you won't get these diseases", which is important, but there's also a need to talk about masturbation, for example.

It's important to talk about the diverse spectrum of sexuality, because the other side of that spectrum is pain with sex, which is where this game came from.

👻 Your projects often invite players to slow down, to sit with discomfort or tenderness. What role does emotional pacing play in your design choices, and how do you think about interaction as a form of care?

I was really hoping you would ask about this, because I did want to talk more about reflective game design.

For (val)iant), I really wanted to use reflective game design principles in the experience.

Just to talk a little bit about what that is, I believe it was Rilla Khaled who coined that term. With reflective game design, we're bringing people out of immersion. In commercial game design, so in the mainstream industry, we want people to have as much fun as possible, because if they are having fun, they're spending time on our product and they want to come back for more; they're going to give us more money.

And in reflective game design, we question what happens if people aren't immersed. What if we take them out on purpose? What does that mean? And I was really curious about that because I loved this concept of complicating things and making it not fun on purpose.

And it worked perfectly with the theme: I wanted to make a game about chronic pain. That's the whole point. So it's not something that's supposed to be fun and pleasurable for most people. It's not fun at all.

So to go back to the question of emotional pacing, right at the beginning of (val)iant), I really wanted to hit hard and use reflective game design to make people think about their own experiences with not just sex and their own sexual health history, but also talking to doctors, for example.

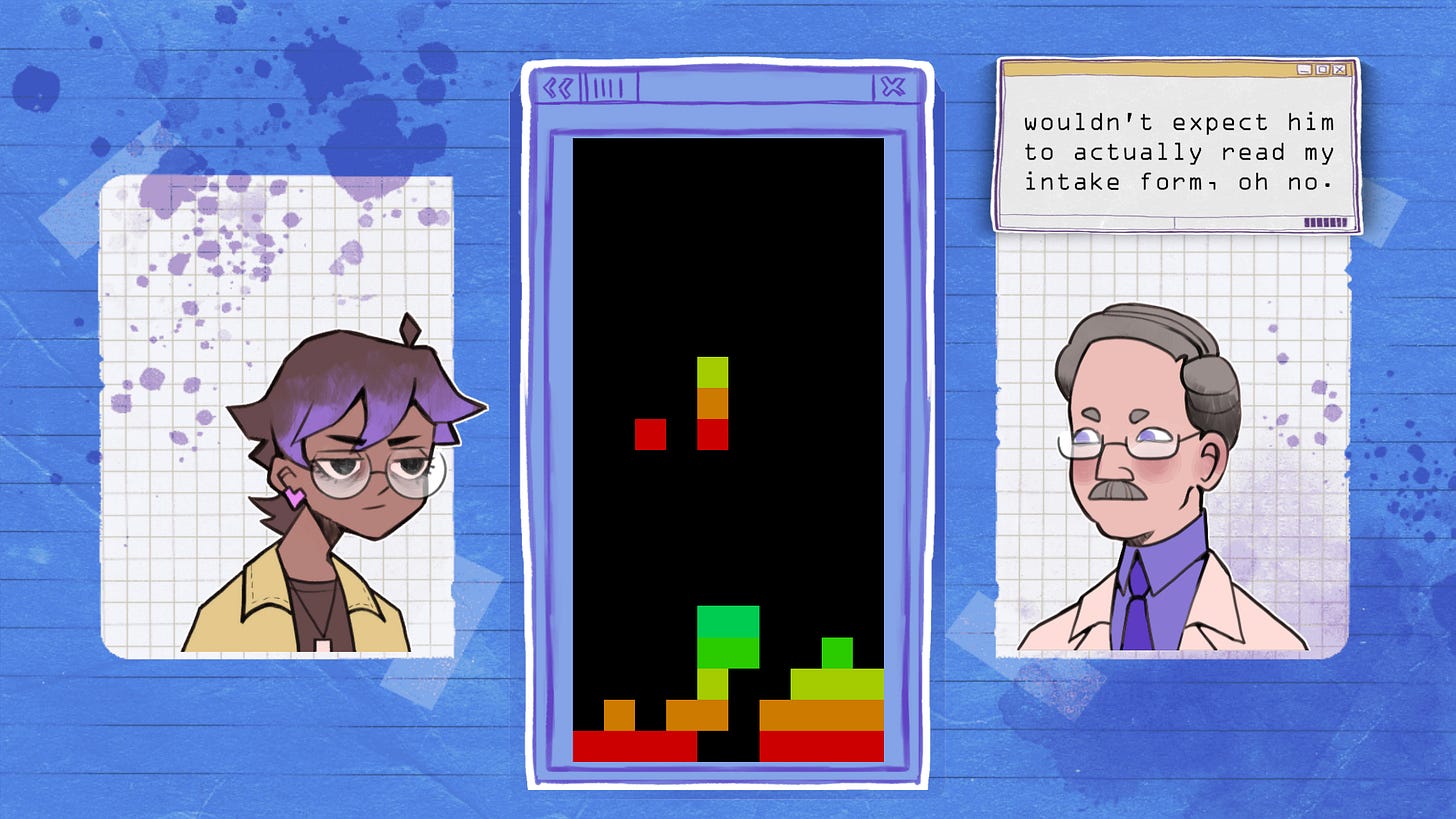

Like at the beginning of the game. While Val talks to the doctor, you are playing an impossible Tetris game. You're trying to do the best you can and it's just not working. And I did that because I wanted people to reflect on what it’s like when medical professionals don't take you seriously.

So I wanted to communicate the feeling of not getting the care you need. Not being able to talk about sex with your partner. That’s where those impossible minigames come from.

That does change over the course of the game. Our goal was to show that Val finds community with other people, finds better providers, and meets new partners. She meets new people with new attitudes about sex and sexual health. You can see their evolution: “I can learn to enjoy sex, or maybe I can find someone who can give me better care”.

And we showed that by contrasting gameplay in different parts of the game. The start featured those impossible-to-win minigames, when the world was closed off. And the other more positive parts of the game are more creative; and when the player has more agency to make things, it feels like the world is opening back up again.

A concrete example of that would be the second Doctor you talk to. It's Tetris again, but the blocks don't fall: the player gets to control where they go. If the blocks aren’t falling, is it even a game? Is it even Tetris? We’re expanding our concept of what a game is. And our desire with this was to show that Val was expanding their mindset around sex and sexuality, thanks to the people that they were meeting.

So the minigames transition from something impossible to something slower and more creative, where you can go at your own pace and be in control. We introduce curiosity back into the game, whereas in the first half it’s just challenging and frustrating. So that was the interplay between plot, message, game mechanics and emotional pacing.

👻 As someone researching and developing games for sex education, what gaps or possibilities do you see in how games can shape conversations around health, consent, and bodies?

I love this question because this is what guides my everyday work. I think there is a lot of research that could be done. But I’d say people are just starting to take games more seriously, not just as an art form, but as tools that can achieve a clinical purpose. So regarding serious games, not only can they be used in education, but also as clinical interventions.

My experience mainly comes from where I’m based, with the U.S. sex education system. It’s undeniable that we don't have comprehensive sex education across the country. And it's actively harming women and people with vaginas. It's harming everyone, and people can’t get care. But honestly, as far as more material outcomes go, I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that not having sex education, not having education on consent and intimacy is killing women.

But where do games fall into that? I think the first thing to acknowledge is that we just need to fund sex education more; And under the Trump administration, goodbye to that, right? That's not happening. There are so many organisations that do it out of the goodness of their own heart with very minimal funding, trying to ameliorate this terrible system that we're in, but it really is a systemic thing. That is a huge issue that can't be solved by one nonprofit.

But part of my interest in games for sex ed is selfish; I do it because I like games. But I think in my very preliminary research, I did come across a lot of people who are making games about topics that have to do with intimacy and sexuality.

And why might that be? Why are people caring about this topic? I think that’s because students learn the best when they're having fun. If they're not having fun, they don't give a shit about what you're teaching them.

So even before I studied games, I was always trying to incorporate fun and play into lesson plans because I really wanted to make my classes as seamless as possible. I wanted students to enjoy what they’re learning and thinking about.

And games are a great way to do that because they give people agency. You're making those choices. You're embodied in that narrative. It works for education in general, including sex education.

In classrooms, most people get really embarrassed when we're talking about bodies. But what if you had a digital game that you could play in the privacy of your own room? Kids these days are already doing that on the internet, which is basically where they get their sex education. And that is a good and bad thing, right? Because it's usually either from porn or it's from Scarleteen or YouTubers talking about “what's going wrong with me and my body” and “when I get my period, what does this mean”, you know? They're not really getting it in the classroom.

Personally, I believe it's very important for young people to have a trusted adult they could talk to about bodies, intimacy, consent, and sexual health. They shouldn’t be alone. As much as I love the internet, and it is a very vast resource for sex education, including games, youth needs a teacher or a parent or a guardian. Someone they feel they can trust to talk about these things.

In my perfect world, I would love to make digital and non-digital games that young people can play on their own or with a trusted adult, or both: maybe one part is for the trusted adult, one part is for the teen, and then they do something together, right?

Introducing that sense of play into it makes it less scary and less boring. Well, at best, less boring, at worse, less scary. Because sometimes sexual health topics are scary for young people to talk about, especially things like consent and sexual assault, which are very heavy, deeply personal topics.

So as I said, it's a bigger systemic issue of “how do we change sex ed?” But I think that games can be helpful because they are playful. Certain games, like digital games, you can play from the privacy of your own room. Maybe there's a mobile game on your phone that you can engage with at your own leisure. And games are replayable, right? So depending on what kind of game it is, you can embody a specific character, choose things, make mistakes, and there's no consequences; and there would be in the real world.

And you also learn from the narrative, kind of like an interactive book. This game has a character, and instead of reading about their story, I am engaging with it. I'm playing this character. I'm understanding their emotional plight.

And it doesn’t stop with education. Games can also work as clinical tools. I am very interested in patient narratives and narrative medicine. I think telling stories about our experiences as patients, and even more broadly, our experiences as people who have sex or don't have sex, is a great way to learn about the world around us.

So I believe interactive storytelling, which is what games excel at, is very powerful. The stories stay with you. I think I'm really invested and curious to learn more about medical narratives in games like (val(iant) and how that can help youth understand their own bodies, understand their own history of sexual health.

👻 Finally, what’s inspiring you lately? Are there any games, animation, books, fanfiction, or anything else that’s been fueling your creativity?

I love these questions because this is how I get more additions to my list every time I read interviews that you've done!

I have to shout out a couple texts that were essential to me as a designer, one of which was “Rise of the Videogame Zinesters” by Anna Anthropy.

Oh, I'm reading this great book called “Critical Hits: Writers Playing Video Games”, edited by Carmen Maria Machado and J. Robert Lennon. It's a great collection of essays from writers talking about video games and experiences with games, either making them or playing them.

To combine the different sides of my life – literature, video games and public health – I have been reading this book called “When Sex Hurts”. The authors of this book are some of the leading experts on chronic pelvic pain, and they wrote this book for their patients. I’d recommend it to anyone who thinks they may be struggling with vulvar, vulvovaginal, or pelvic pain. Or anything else, more broadly, like pain with sex, frequent/painful urination, pain with pelvic exams or tampons and more.

The authors of “When Sex Hurts” are actually the medical advisory board of a non-profit I work with, Tight Lipped. It's an amazing book whose audience is meant to be patients who have pelvic pain, so someone like me. But from a narrative medicine standpoint, as a provider, you can read this and be like, “I had no idea that patients feel this way”.

“Is Sex Education An Intelligible Concept?” by Lauren Bialystok is one of the best essays I’ve read in the last 5 years; it’s directly relevant to anyone in the practice of sexual health education. It definitely complicates what 'comprehensive sex education' even means, but that's a good thing. I quote this essay ALL the time.

The “Games for Health” book by Sandra Danilovic is a very accessible work that helped me define the kind of games that I create and care deeply about. The idea that “games for creative health” are just as valuable as games for clinical health interventions is one that I want to champion, alongside Sandra!

“Pleasure Activism” by Adrienne Maree Brown is an incredible feminist text and essential reading for all people with vaginas. "How can we awaken ourselves to make it impossible to settle for anything less than a fulfilling life?”

“Queer Games Avant-Garde” by Bo Ruberg is one of my all-time favorite texts on games.

Now regarding games, dys4ia by Anna Anthropy was one of the biggest inspirations for (val)iant. She has made many more incredible games beyond this one, and I know it's one of her older works, but it really is an all-time favorite for me. I first played it in 2016 and it changed my entire outlook on videogames and what they are capable of doing. It goes into her experiences with hormones and hormone replacement therapy.

And you mentioned Florence, which is another huge inspiration for (val)iant for different reasons. And from a purely “I just like this game a lot” point of view, What Remains of Edith Finch is one of my favourite games of all time. I guess it is related to my work somehow, because it's about storytelling, and it’s the style I like to read.

This is Normal is an incredible infogame my friend Anna Krasner made with a few more people. It talks about self managed abortions, and I share it widely whenever possible. It's simple and informative; you can finish the game within 15 minutes.

You can check out KB’s work on her website, or on her itch!

— The ghost that haunts the intersection between games and education,

almoghost.exe (or André Almo if you’re feeling serious) 👻

Excelente