I have recently come across Jordan Magnuson’s concept of “game poems”: short-form video games that function, essentially, like a poem. You can see more about Jordan and game poems in his recent interview for LudoSpectre!

Since then, I’ve been connecting to other game poets – aside from creating my first game poem in the process (more on that in the future)!

One game poet whose work I’ve recently run into is Brendan Allen. Brendan (also known online by the “bibliomancer” moniker) makes small games that linger like stanzas. He’s an educator, writer, and game developer.

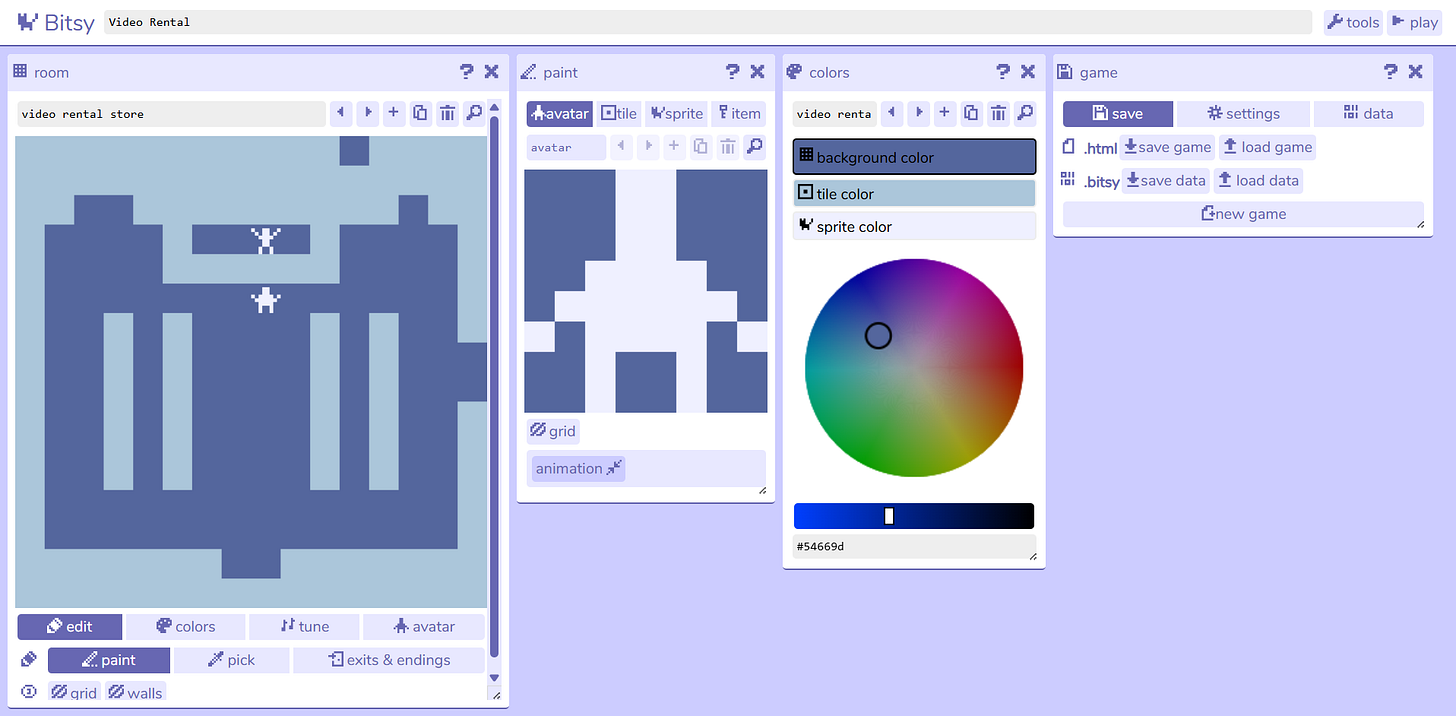

Blending poetry and interactivity, his work explores how minimalist tools like Twine, Bitsy, and PuzzleScript can become vessels for deeply personal experiences. In games like Correspondence, The Last Best Western, and CentoQuest, Brendan invites players to navigate not just digital spaces, but poetic ones.

In this conversation, we talk about his inspirations, his process, and how constraints can unlock power and expression.

👻 I’d like to start with a quick look into your practice. You are an educator, writer, and game developer. How did these things come together?

I think like many people doing creative work, this is probably a weird and complicated answer.

Games have been a part of my life for a very long time. But for much of that time, it was something that was always separate from my creative practice.

It was a space for leisure, and I was also experiencing games as art, surely. But having no programming experience — coding wasn’t something that I had been exposed to as a younger person — it always seemed so far outside of my capabilities, technically speaking.

Whereas using a pen and a piece of paper to write a poem felt much more feasible to me.

So, you know, all my life, I've been playing video games and reading a lot about them. Video games can be a very expensive hobby, right? And growing up, I didn't have every game out there, so I was constantly absorbing something that now seems totally obsolete: video game magazines. Yeah, exactly, magazines, in print. Yeah, mailed to my house.

I'd get like, five a month and I would just spend a lot of time on them. Whatever games that I couldn't play myself for various reasons, I would just be reading about them, imagining what that experience might be like.

So in some way, video games — even when they were just firmly in this leisure space, especially during my childhood — were also still kind of in this conceptual space for me, because I was doing so much thinking and imagining of how they might work, especially if I was just conceiving them instead of actually playing.

And from about the start of my undergraduate career until present, I've been working as a poet. My experience in university and in graduate education has been almost entirely in poetry, looking at critical understandings of contemporary poetry, but also creating my own work.

And in 2019, I started a Masters in Fine Arts at Temple University. In this programme, suddenly, the bulk of my time was spent actually creating my own work. And there's nothing like having that availability of time to make writing poetry incredibly, incredibly hard.

And so I was in this really wonderful creative writing workshop run by the poet Jena Osman. It was called “Poetry in the Expanded Field”. This was a workshop for poets, people who are explicitly studying and writing poetry, along with visual and multimedia artists. So we were a group of interdisciplinary, hybrid creators.

So we were all working and making poetry in the fullest capacity. The whole point of the workshop was that we would use all these different materials each week. Every week there was a new prompt.

I don’t even remember what the prompt was, but one week, it was something about poetry as a digital object. And for some reason I just could not bring myself to write a single word, a single line of a poem. The amount of labour of just writing one line… I just could not do it.

And I thought, “Well, whatever. I'll just make a video game”. No video game experience, no idea what that meant. I had come across Twine, the tool. And I thought, “That's all text-based. How hard could that be? I bet I could just whip something together in an evening”.

And no, of course I couldn’t.

Fast forward to three nights of me staying up ‘till three in the morning in a row. And then I had created this little thing that was the prototype for CentoQuest. That was the initial seed. And then I realised that I was just returning to the project more and more and more, and getting really excited about the way it made my brain think and organise language.

And I think from that point I just started reading a lot more critical and creative works about video games. like Anna Anthropy’s “Rise of the Videogame Zinesters” and Jordan Magnuson’s book, “Game Poems”.

The combination of those texts and a few other ones made me realise that even though I had no idea how to make those things, there were ways in which I could figure it out, and that could be a productive thing to do.

👻 You usually focus on quite constrained game making tools, like Bitsy and Twine. What creative potential do you see in them? I’m especially interested in your view as not only a game designer, but a creative writer.

I think some of the things guiding my initial choices were less conceptual and abstract, and more pragmatic only. I'm still very much at the point where every time that I'm making a game, I'm actively learning how to do the things I want to do.

There's so much of just googling Stack Exchange, reading Reddit threads and just piecing together what I know for a fact has to be the world's ugliest, most inefficient code in these already very constrained systems.

So the first question for me is often: “Do I think I could figure this out, relatively on my own, in a feasible time frame?” So that in itself already pushes me towards constrained systems, like Bitsy. There's no programming even needed. You can code in it if you'd like to, but it can all be just a visual system.

And this hybrid genre of game poems is so well-aligned with that. I find that constraint as a concept — and I know this is something that Jordan talks about in his book as well — is really invaluable for pushing yourself into a new way of thinking, which I think is the core of poetry in a lot of ways.

And I think creative work is very much about how you take these systems around you and within those constraints, make something new, make something that excites you, make something that isn't just resisting these rules, but is actually using these rules to its own benefit.

And poetry is really good with that because you're usually working in a pretty small physical space. Or you might be working with even more rules if you're writing a sonnet or a villanelle, right?

And I find making a game in these very constrained systems to be a bit like that. Suddenly you only have this much space. Suddenly, you only have three colours. You know, every choice you make is kind of pushing you to make creative choices that you might not otherwise make if you were just staring at a blank screen with ultimate freedom.

👻 I usually think about what are the limits between interactive fiction and games, especially with things like visual novels or text-based games. I think there is a huge overlap, and maybe many of these products are actually both interactive fiction and a game at the same time. That’s something that crossed my mind as I was playing CentoQuest. What was your vision for it? Did you approach it as a game, as interactive fiction, or both? And what are your thoughts around this?

I think this is a great question because I think about this, even just with poetry, all the time. When I organise poetry or creative writing workshops, the most frequent question I get is “Well, what is a poem?”, which is a terrifying question to receive in the classroom.

I have students who feel really strongly that if it doesn't rhyme, then it's not a poem. But we can just take a look at the overwhelmingly large collection of poetry that is actively not interested in rhyme. And of course, rhyming creates a certain sensibility in a poem, but then again, choosing to resist that sensibility is also interesting.

And we can also discuss prose poetry, right? You can have a prose poem that at a glance looks like a paragraph, but why is it that the poet has classified it as a prose poem?

You have epic poetry that is the length of a novel, right? And then you have things like digital poetry, interactive poetry, game poems. To someone who's just been studying 18th century lyric poetry, this may all be unrecognisable in a lot of ways.

I'm willing to acknowledge this, though: I sometimes have a far too expansive notion of what constitutes a particular genre.

And a lot of times, I'm very interested in trusting the creator's choice to label something as an intentional engagement with that genre. So if someone comes up to me and they hand me three pages of a full wall-to-wall text with no line breaks, no seeming internal rhyme scheme or rhythm, and they say, “This is a poem”... my first thought would be “okay, I'm going to read it like it's a poem”. I would bring everything that I bring when analysing a poem and see what that reveals of this piece.

So what I really like about game poems as a genre is that it's such an amorphous kind of genre distinction right now, which I think is a strength.

You go on itch.io and you see people saying “this is a poem”, or a “not game”, or an “anti-game” experience all across the platform. And on a side note, I just love that itch.io lets you designate things with a custom noun. I don't know if you've seen that, but it just makes it an even more flexible territory.

So regarding CentoQuest, it is a text-based game that has this embedded narrative to it, but it's also a tool for writing poetry. You explore a house and interact with books and objects around it, getting verses that you can then use to write a patchwork poem.

There is a moment in the game which started as just a very silly joke: you go into the kitchen and you can open up the fridge and you can pull out everyday ingredients from it.

So you've been working with these books of poetry and pulling lines from them, but then you open the fridge and there's like a jar of mayonnaise, which you can pick up to look at the label. And then you can choose to take things from that label and put it in the poem.

While this is very silly, it's also a very important exercise about language and creativity: what happens when you look at this jar of mayonnaise and you think about the text on it as having poetic capacity?

I mean, if someone comes up to me and they hand me a jar of mayonnaise and they say “This is a poem”, of course, there would be an alarm bell in my brain. Is this for real? But I think it is productive to approach those kinds of experiences with curiosity.

👻 And on a side note, I can totally see that happening. I could 100% see a poem in which you take an ultraprocessed product, you know, these heavily industrialised and processed “food” products, and just list all the chemicals and additives you find in the label. And then there is a message there: what are those ingredients? Is that even food? Should we be eating this?

What you just described, I know for a fact, there are poems like this. Like, people are doing that work.

There's a contemporary conceptual poet named Kenneth Goldsmith, and a lot of his work is taking these existing blocks of traditionally not-very-poetic-seeming-text, like a news report or a traffic report of a certain day, and presenting it as a work of poetry. I don't know if he's done anything in terms of processed food chemicals, but I bet someone has. I would not be surprised!

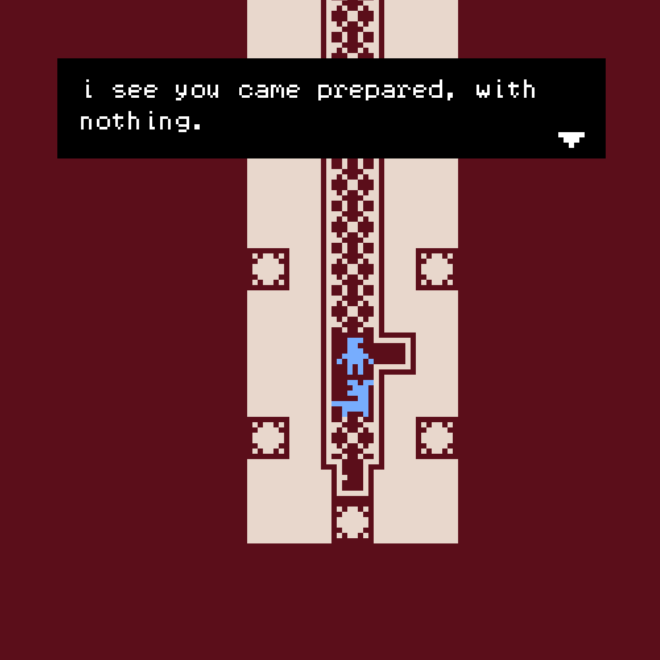

👻 Now let’s move on to a game I absolutely loved: The Last Best Western. I felt so immersed in that setting that seems to mix Americana, decay, and solitude in a kind of looping journey through a decadent hotel. What drew you to this setting and tone? And how do you think Bitsy – the engine you used to craft the game – influenced the final product?

First of all, thank you for playing this weird game. It feels like only 11 people ever played this thing.

👻 And as a Brazilian, I also appreciate that “Garota de Ipanema” was playing. Aside from being a classic, it’s such a hotel-y song. Its instrumental versions have become kind of an elevator music cliché, right?

I'm touched that you noticed it! But it also feels very silly because it's made in Bitsy. Which I think is a good test case for your question, because the game only exists the way it does because of both Bitsy and some of the reading I was doing about game poems at the time.

I had been reading Anna Anthropy’s book “Rise of the Videogame Zinesters” during a kind of long cross-country drive, which was a very solitary drive.

I was just by myself in my car, car camping, and it was getting kind of rainy and wet… and I was sick of camping. So I pulled into this random hotel; it might have been in Ohio, it might have been in Pennsylvania, but it was in that area.

And, you know, it was one of those times where you're in-between jobs and responsibilities, so you don't really have the pressure pushing you to the next thing. So it felt like a very liminal moment… which random American hotels are great for, they fit that liminal space experience really well.

And all of that was happening at the same time as I was reading Anthropy’s book, which has this really lovely section with a list of all the things you might make a game about. It’s like, six pages of ideas: “make a game about your boyfriend”. “Make a game about your girlfriend”. “Make a game about going to school” and “make a game about getting kicked out of school”... and then it came to me: “make a game about the time you were lonely in a hotel in Ohio”.

And if you're looking to make a game about the personal, the autobiographical, the thing you have the most embodied experience with is a great place to start.

And that got lodged in my head. I knew I wanted to play with Bitsy, because I had never actually worked with it myself. So the first thing I did was just a mock up of this weird little liminal corridor in Bitsy. And it kind of evolved from there.

And a lot of what’s in the game is an artefact of me learning how to use the system. The reason “Girl from Ipanema” is used is that I needed to teach myself how to use the Bitsy music maker, and I'm not a musician; I cannot reliably read music. But I really wanted to figure out how it worked, and also teach myself how to read music in a certain way.

I opened the Bitsy music maker and a music sheet for “Girl from Ipanema” and then guided myself through the process of transcribing that to Bitsy. And at the very end of the game, I did the same thing for “Hotel California” by the Eagles.

👻 I really like this part of solo game development. We just push ourselves to learn how to do everything, right? Be it coding, illustrations, music, or sound effects.

I think another amazing strength of small, constrained engines is that they make game making feasible for one person.

And that's not to knock team-based projects, but it’s something really important to preserve: the unity of focus that a solo project can have.

👻 Yes, and it can just be a small project. It doesn’t need to be like Eric Barone’s Stardew Valley or Toby Fox’s Undertale.

When I think of Eric Barone and Toby Fox, wow, no one should be comparing themselves to those. I do not know how those people do all that work, it's just amazing. Every time a new Stardew Valley update comes out, I'm like, “how have you done this”?

But I'm glad you brought up Undertale, which is an amazing game. And I know that's not a bold statement. A lot of people think it’s amazing. But for me, playing it for the first time was one of the early experiences I had in terms of actually finishing a video game, and having this feeling that it wasn't just a good video game… it made me want to make a video game myself.

I get this with poems a lot. You read a really good poem, and your first thought is “that was an amazing poem”. Your second thought is “how did that person do that”? And your third thought is “I really want to sit down and write a poem now”.

And if you read into it, a lot of Undertale was Toby Fox just learning to develop the game within GameMaker. I went down into a huge Wikipedia rabbit hole where I learned that he actually started out in game development by creating these fan-made Earthbound hacks.

There was something about that that just.. helped something click for me: “I don't have to start by making some kind of transcendent artistic experience, but I can take these little things that I already know how to work with, and combine them in interesting ways”.

So it was a very inspirational game to play, because weirdly enough, it made it seem that I could make something that is an artefact of me trying to figure these systems out.

👻 Correspondence is your latest work. It’s a good example of a poetic game made without any text, kind of like Jordan Magnuson’s Loneliness. How did you approach that challenge of evoking a certain feeling through a puzzle game with no text? I would say you nailed down the experience of managing an inbox, and the art was so reminiscent of a 1990s Windows.

I'm both glad and touched that you asked that question, because that was actually the guiding thought I had in mind. I had been working with language-based poetry for so long, it is intuitively where I moved towards in my creative practice.

And so it emerged from a constraint as a challenge to myself: “can I make a game poem with no language whatsoever”? And that's kind of a cheat because there is a title and there's a little win message at the end.

And then the rest of it was a lot like The Last Best Western, and connected to that call-to-action in Anthropy’s book.

The game was very autobiographical, because it was at a time in which I had a job where I was constantly answering emails. And there's nothing I could do. I would send one email and two would come in. The more I responded to emails, the more I would get.

I felt like Sisyphus, tasked with forever trying to beat my inbox. I think it was also born out of this dream of “what if I just throw it all out”? Like, if I could just throw it all in the trash, then my inbox would be empty.

The interesting thing, though, is that the trash bit emerged as I was making the game. Originally, it was just me figuring out how to use PuzzleScript to code the very basic functionality of a Sokoban game, which is just a push a box.

And in this game, the boxes turned into the emails: “I'm pushing the emails to the endpoint. Great. That doesn't feel very fun”.

And then the challenge was how to represent, within this very limited visual palette, what it means to receive an email. And then how it feels to receive an email when you're in the middle of writing another email. And then, how it feels when you look away from your computer and suddenly you have 10 more emails.

And thanks for mentioning the design, too, because honestly, I would say I spent 50% of my time on that game making the system… and probably another 50% figuring out how to use the system to make it resemble that Windows 95 space.

I find that very interesting as an artist: there's all of this hidden work that goes into making a game. You just glance at a thing, in any game. Stardew Valley, for example: he made a patch of dirt, and you can put a turnip seed in it and the turnip grows. Cool.

And beneath that, there are so many systems that are tied to not just how fast the turnip grows, but the sound, the haptics, how it feels to drag your hoe across the dirt, even though it's this tiny pixelated space.

So I think making any game is also great for teaching yourself that all of these very simple things are built upon really complex systems.

Like, my PuzzleScript game is very easy, but it's built on this very complex engine created by Stephen Lavelle (who goes by Increpare).

That happens in poetry too. I think there are just fewer visual artefacts pointing towards inspirations. “Why did you come up with this word choice?”, you could ask a poet. And they would answer: “Well, to explain that, I have to tell you about how I took this walk and on that walk, I encountered this particular view. And then while I was looking at that view, I thought about my taxes, and there was a word in my taxes that reminded me of this”. To try and communicate these things without any kind of visual evidence is really hard. So I like the visual evidence games bring.

👻 This is true. Correspondence has Sokoban and Windows 95 as its core elements, that’s easy to see. And again, I do think it translates the experience of never-ending emails pretty well.

Well, I really want to thank the Puzzle Script engine for that, because it comes with all these ways to generate little sound effects that are slightly randomised. So many of them are these little, cheery blips or blops, and there's something about when your email client has noise attached to it. This “ding!” that the client uses… it wants it to feel like, “oh, it's exciting”. “You have a new email”. But when you're tired, there is a really small distance between the cheery blip and “I hate my life so much right now”. The sounds that are generated from Puzzle Script were very helpful for generating that frustration.

👻 I always like to end my interviews with a few recommendations. Any books or games that you’d like people to go after?

I’d love to drop a few recommendations! I think so much of my practice is based on me encountering work by others and getting inspired by that.

I will start with two games, which are very silly in a way, but really critically-oriented and very interesting. And so the first one is called Fast Car by mut. It is a lovely browser game about finding your friend in a desert and going on a little road trip. And it does remarkably interesting things with plundered assets and using music as a kind of emotional register.

The next one is Bluejewelled by Brandon Hare, which is a hack of Bejewelled, where... without spoiling too much, it just replaces all the gems with blue gems. But then it pushes that to its logical extremes. And I think it actually raises some really interesting questions about feedback and the kind of overwhelming dopamine rush we get from games.

Nice. And then, there's one called a farmer and his fields, bound together by deimos. that is, again, a very small kind of constrained thing made in PICO-8.

So those are the three game poems that are constantly just swirling around my head right now.

And some other poetry recommendations… there's a poet named Marianne Moore who is a major creative influence for me because her work involves a lot of collage, in terms of taking the lines and texts from different sources and combining them into new configurations. She has this poem called “An Octopus” that is very much built out of these lines.

I mentioned my old advisor, Jenna Osman. She has this really lovely digital poet group piece called “The periodic table as assembled by Dr. Zhivago, Occultist”, which for me was also a really early influence and exposure to what an interactive poetry experience can look like. Osman wrote a poem for every element of the periodic table and then you can actually use this interactive table to combine the elements in various ways, with various reactions, like dissolving them, stirring them, heating them. And those elements then combine procedurally into new poems.

I also find Aram Saroyan's minimal concrete poems to be a major influence and provocation, especially in terms of extreme constraint. How does a poem do its work in a single glance? And how does it get the reader to come back, glancing again, and finding something new? I’d also like to recommend both "lighght" and "m."

And Harryette Mullen's Sleeping with the Dictionary was a really meaningful book I encountered back in college, when I was first starting to write poetry -- it helped me see how the language of a poem can have the capacity for critically-oriented play. I still think about that book a lot when remembering that the pleasure of crafting a piece doesn't have to be divorced from the thing it's "figuring out/arguing/challenging."

A lot of my creative process also involves collage-style combinations of both text and media, which is one of the reasons I love Marianne Moore so much.

Mark Nowak's work is also a major influence for how I think about the capacity for political and rhetorical arguments with these methods. What does it mean to put one voice up against another? I'm not sure that this is super evident in my own game poem attempts so far, but I do see it in a lot of others' work: that the tools of playfulness are also tools of critique.

You can check out Brendan’s website here, or take a look at his games on itch.io!

— The ghost playing game poems while you sleep,

almoghost.exe (or André Almo if you’re feeling serious) 👻

I wrote a poem in CentroQuest it was really fun I’d like to come again.

thought and count: between diarrhea and constipation,

Toward morning, walking along the river,

but help yourself to what's here.

The arc of stars

Could I clean them in the creek?

move to dress

I could climb — if I tried, I know —

Hello from another gaming-related Substacker!