What are games, really? The academic definition would say that games are a structured form of play, with clearly defined rules and objectives. But humans are really good at turning things — and their meanings — upside down.

Jordan Magnuson is one of them. He is a game designer, artist, writer, and lecturer in Games and Media Art at the University of Southampton. He has made different types of games, and some have been defined with unique terms: “art games”, “game poems”, and, perhaps most surprisingly, “not games”.

Known for his minimalist, experimental approach, Magnuson explores the intersection between interactivity and emotion, often using digital spaces to meditate on memory, travel, and the human experience.

He’s been pushing the boundaries of what games can be, pioneering the field of games as art — inviting players to pause, reflect, and feel, rather than just win or lose.

His work asks us to reconsider how we define a “game” and what it means to play.

👻 How did you first get into gaming as a hobby? And what about game design?

It is something that goes back a long time for me. My relationship with video games has had all these different phases. Actually, there were points where I felt unenthused about it, like I'd kind of seen what there was to see. There just wasn't the same amount of interest or depth that I had felt for things like literature, philosophy, history or whatever else, you know?

My dad had one of those first Mac computers, and he was writing his PhD dissertation in North Africa at the time. He was a cultural anthropologist. I remember playing a couple of those early games that came on the Mac, like um Stunt Copter (1999), a duck shooting game, and an elevator game. So that would have been back when I was maybe five or six. I found them interesting, but not necessarily exceptional.

I never had any consoles growing up, but we'd occasionally come back to the States and people would have a Super Nintendo or a computer with a game or two on it. And eventually, I started being kind of more intrigued by some of these. One of my friends had a Game Boy and we'd have sleepovers, sit under the covers and just play it until the batteries died, at 3 or 4am.

And there is something special when you’re a kid. I look back now and oftentimes there were these rather brutally difficult games that we played. As an adult, you’ll meet those challenges and you’ll be like, well, “this is impossible”, and give up in a minute.

But at the time, as children, we had that sort of mysterious infinite amount of time somehow… you’d sit there, and try again and again, and get a little bit further. There was that feeling of, “oh, what's next”? That extremely powerful draw of “what's going to be on the next screen”? “What's going to be the next part of this game”?

Eventually as I was getting a little bit older, I guess between 10 and 12, I ran into some of these more complex computer games. Friends showed me things like Star Wars: Rebel Assault, you know, some of the first Star Wars games by LucasArts that were pretty cinematic, and some adventure games.

Somewhere along the line, I ran into a friend who had SimCity 2000. That game was my first true love, and sparked my fascination with computer games. We were staying with these friends at the time, and I just remember people asking “where's Jordan”? And had just been playing this game for ten hours straight.

I think SimCity was the game that kind of brought home this realisation that there’s almost anything you could do with computers, right? A much larger possibility space than I initially had realised when I was younger and playing relatively simple games.

And SimCity, this whole thing of building and planning and simulation really excited me, because I had always had that creative interest. I'd always been drawing and painting as I was growing up. I was building things, and that game really tapped into that.

From there, going into my teenage years, I was playing a fairly wide range of PC games, especially strategy games. Games like Civilization and SimCity, but then also RTS (Real Time Strategy) games, like Age of Empires and StarCraft.

As I was becoming more interested in video games, I started imagining my own games. I think this was probably true for a lot of kids. You play games and you start imagining – maybe even if you don't have any idea how to make games – what kinds of games you could make. And I had a notebook where I would jot down game ideas and whatnot.

And then I was lucky. One of my dad's friends saw that I was intrigued by computers and whatnot, and basically ended up giving me programming lessons when I was like 11. At the time it was Turbo Pascal, so no GUIs, no graphics, just, you know, getting into programming.

I realised that the world building aspects, the simulation and all that was happening in the background didn't really rely on graphics anyway. So I could actually start programming these worlds, even if they were all textual.

And I remember trying to create a vast open world space simulation, where you would go to different planets and do different things, all in Turbo Pascal. And then eventually I got onto things like Klik & Play and some of these early game builder engines. These engines made it easier to just put your graphics in and do all this stuff.

And during the mid-to-late 1990s, when the Internet was still fairly new, there were certain sites that would have free, shareware games, which were kind of popular in the US at the time. But still, there weren’t many.

And I got onto these little communities of people making games. Later I ended up going to university, and I was still making games, although I also got interested in other things. But by then I had started a little website called The Independent Gaming Source, because I was interested in this idea of games as this “art house of ideas”.

And during the late 1990s, early 2000s, there wasn't really much community for that. So it ended up becoming a hub of sorts for people interested in this idea of “hey, let's make weird, cool, interesting games, let’s do different things”.

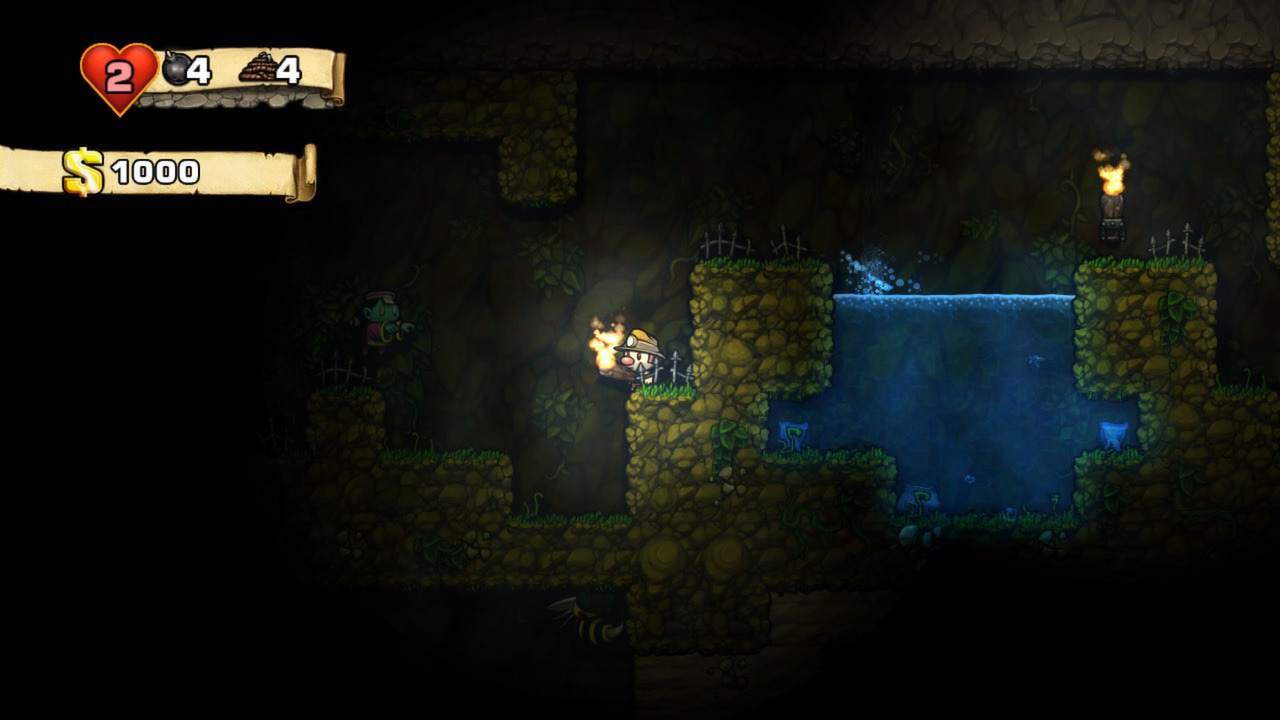

I don’t know if you know Derek from Mossmouth who worked on Spelunky and UFO 50. I first ran across some of the games that Derek was making with his high school friend at the time back in the late 1990s. Anyway, I ended up passing that site onto Derek, actually. So he ran that site for most of its life. It had about a ten year span of being a significant space.

Anyway, at the university, I was taking philosophy, aesthetics, art history classes, and got interested in this question of games as art, and started diving into this. These were the early days of those conversations: “are games art”? And I ended up writing my undergraduate honour’s thesis: it was a paper on video games and art.

And then I stopped being this focused in games for a while. My trajectory resembles waves, sometimes more game-focused, then other things-focused. But eventually I played some of these early art games, like Passage. Some of Gregory Avery-Weir’s early games, like Majesty of Colors, things like that. That got the sparks going again for me.

I got intrigued by the idea that you could use the basic building blocks of games to do different kinds of things, things people weren’t doing much back in the late 1980s or early 1990s, right? That you could use these same simple technologies to just do different kinds of things.

I got really excited about that and just started making these weird little experimental games; it basically got me onto “game poems”. Mostly because I was making these kinds of games for a few years and always struggling to explain what I was doing to people. And eventually the language of poetry clicked for me as something really helpful.

👻 It’s great that you wrapped up your journey by mentioning this, because that was my next question: “game poems”, “notgames”... what do these terms mean?

To me, the exciting thing about the “game poems” idea was just proposing some language that might help us to see something fresh, or approach games in a slightly different way. And my idea was never for that to be a rigid term, by the way. It’s just stimulation and something that might help with appreciation of some kinds of games.

Over the course of the time I’ve been making games, I've tended to refer to them in a lot of different ways. I've called them “notgames”, for example. I got really intrigued by the “notgame” label for quite a while.

So, there's these two artists, Michaël Samyn and Auriea Harvey, who made this game studio called Tale of Tales back in the early 2000s. Some of their games were really artful, like Passage. They were inspiring games, like The Graveyard. The Path was another one. They tended to make 3D games, and they were using these video game pieces to make very different kinds of experiences.

They got really interested in this idea of “notgames”. So that was the term that they proposed. It was just this idea of “you can do so many interesting things with the technology and all these different aspects that video games are using as a medium, but video games have kind of got trapped in a particular way”, right?

There were so many possibilities, so many things that could be done with the same sort of representations, the same sort of computational processes, but that weren't in the mold of traditional video games. And that was the idea with “notgames”.

They wrote this “not a manifesto”, which was a short little manifesto about “notgames”. But basically it was just kind of a design challenge: “can you make video games that are just not like video games”? “Can we try to make experiences that aren't bound to these traditional ideas of what a game has to be”?

So I got really inspired. They had a forum at the time and a bunch of designers were in there, and I found that to be a really inspiring place. It was a very freeing idea, not being bound by anything. And at the time many people got really upset about it.

Traditional gamers would be like “I want to play actual games, I’m not here to play “notgames”, what is this?”, and then even people who were more open would sometimes get upset about it too, because they'd be like, “well, video games can be anything, so why are you trying to say that these are not games when they are just video games”? Which was kind of understandable, but I think they were missing the point a little bit. This is how these conversations happen, right? The whole point of the “notgame” thing was ultimately to discuss the idea of what a video game could be.

So yeah, for a while, I called all my stuff “notgames”. And then everyone would always ask me about it.

And “game poems”... again, it’s kind of like this. To challenge things, to poke people a little bit. And I very much came to see video games as my medium, it was what I was working with, as opposed to the broader “interactive media” stuff.

And I’ve kind of been in both of those worlds, but my interest has been in continuously pushing video games as an artistic medium, to make them more and more expansive. I’d like to see more people making more types of games, representing more aspects of human experience. People would be able to sit down and have a wider range of expectations than they have historically had with video games.

So a “game poem” is simply the idea that a game can be like poetry. It can be part of the ecosystem of what video games can offer, of what video games can be, right? It doesn't have to be a 200-hour experience, or even a 10-hour experience. Maybe there's also room for a 5-minute experience.

“Game poems” is part of this natural evolution that happened for me as I was, over the years, trying to think about, verbalise and articulate what I was making. “What are these things”? “How do they operate”? “What makes them work or what makes them interesting for some people”?

And I had gone through a decent bit of game studies’, I was familiar with terminology, the history of video game studies, and different lenses that had been applied. But I still kept struggling. I wasn't really seeing anyone offering a robust language that could be used to talk specifically about 5-minute impactful gameplay experiences, so I was dissatisfied.

You’d have games like Passage, for instance. Everyone would say, “Oh, wow, did you play Passage? You should play this 5-minute game, it's impactful, it's poetic”. A lot of people would use this term, they’d throw the word “poetic” around, they’d say it was “mysteriously poetic”. “It doesn't do any of the things that games are supposed to do, but it's still interesting and you should still play it”. People would usually say something along those lines, they’d acknowledge that there was something there worth encountering, but in general, no one could articulate very well why or how.

And I was intrigued because there was this basic connection: it was a short experience, and poems are short. So eventually I took a deep dive. I've always loved literature, and specifically poetry, but in an amateur way. I don't have a background in literature, but then I got into poetry theory, lyric theory, with an interest in seeing if there was stuff there that I could hold on to. Was there any language that I could call on, that would be useful in saying something about these games?

So for instance, my game called Loneliness, it’s the same sort of thing with Passage, but actually even simpler. It's a tiny, 3-minute experience, and it's like a little square moving around. And of course, not everybody liked it. Some people very much hated it.

But I’d also get these emails from people who played it and said “this really impacted me”. So again, this question of “what's happening here”, right? “What is this game doing for some people, why are some people finding this interesting”? Could we say something about it other than, again, that it's “mysteriously poetic”.

So I took a deep dive into poetry theory, and there were times when I was just like, “Oh man, this is going nowhere”, because poetry is so vast. And it is in lots of ways, mysterious, in the sense that there is a spectrum of what can be considered poetry. It's kind of like diving into the whole question of “what is art?” and all that.

So I was neck deep in reading. At one point, I read a thousand page anthology by Jon Cook, focused on 20th century poetry. And I would come back to texts like Jonathan Culler’s Theory of the Lyric, or The Lyric Theory Reader, by Virginia Jackson. And the people who were analysing lyric poetry in particular had a slightly more pragmatic approach rather than having a huge emphasis on the mystical aspect of poetry as art. It was a more pragmatic question of “what is lyric poetry”?

From those readings, I started taking lots of notes, realising it was all extremely helpful. This eventually led me to write the “Game Poems” book, which basically draws a parallel between poetry and games. It looks at lyric poetry theory, and how that lens can help us appreciate certain games more fully, and how it can maybe help someone who maybe looks at Passage and may think it's not a fun game, but may still find it interesting in a way.

So if they look at the game through this lens, it opens up a new possibility. Even if you don't find it to be a fun game to play, or if you have a hard time understanding why someone might like it, this will at least give you a perspective.

So I just found it to be very helpful terminology, both for analysing and appreciating certain games and to define my own work. I finally feel like I have some language to explain it.

And again, I don't mean that in a monolithic or absolute sense, but just in the sense that it's a very helpful term for having a conversation; simply saying, “Hey, have you thought about this”? “What are your thoughts on video games and poetry”? “Have you thought about how a game might be like a poem”?

And surprisingly, this poetry lens had not been investigated very much within game studies. There are little threads here and there, but not a lot. So I just wanted to put it out there, to spark conversation, to push games a little bit.

I know I’ve said this a few times, but just to reinforce the point, this is not to say “Hey, this is EXACTLY what these games are”, or “Games should be poetic”. I don’t want to force it, it’s not a fixed thing. I just want people to view things in a different way, or to have their own views on what games could be. Like the “notgames” term, which was very influential for me, and I still think about that. So maybe I'll be using additional language in the future. It's not my stopping place.

But for now, I’ve been using this term a lot. And in the last year or so, I have been organising workshops on this idea of “game poems” for students, artists, and the overall public. And the most exciting thing is to see the way that poetry lends itself to game design, and makes it so accessible.

People can come in with no game design experience, with no programming knowledge; they may have hardly even played a game before. And what I love about this poetry lens is just the fact that this is all okay.

Everyone can make poetry, right? Of course, it can be a very advanced, nuanced, and sophisticated art form, but it’s also this very approachable thing, and everyone has some kind of experience with it, even if it was back in school. You can sit down and write a few lines, right?

And the same thing can be done with game design. For example, you can take a very simple, accessible tool like Bitsy, and show people how to use it in half an hour. They don't need to have any programming experience. And they can make a little game about something that happened to them today or whatever; it can be this tiny little experience, and it doesn't have to be fun, and it doesn't have to be “gamey” in a certain way.

This is the appeal for me, the idea of pushing games as an art form for more people. This idea that we need more, that we need every kind of person to be making games. Games can represent more parts of the human experience. There are emotions and perspectives that we have explored very deeply with games and others that we haven’t.

So there's this huge need, I think, to make game design something that is accessible and approachable. I think that this idea that it has to be technical, and engaging, and fun, and a 10-hour experience, is not helpful.

So I do these workshops with people who've never made games before and in two hours, I show them how to use a little programme and they make a little thing before they walk out. And this is a shifting experience, right? Who knows? Will they ever make another game? Will they try to get into it? I don't know, but I hope this gave them a little interest, a little spark.

👻 I definitely see the appeal in these “microgames”, and in using games to say something without worrying about it being “gamey”. I think it demystifies it a little bit, and makes it easier on the technical side.

👻 I personally always try to push games as entertainment in my personal life. I recommend games to friends all the time, even if they do not normally play them, or if they haven’t played games in a long time. I think it is so different from other art forms. What do you think is unique about games as a medium?

That view has evolved for me over the years. Two different perspectives have kind of merged together a little bit. Early on, I was highly drawn to and highly invested in this idea that games were so unique, especially going back to around 2010, when I was making these early games and the “games as art” debate was hot.

There was this big defensive feeling among gamers and game designers that fueled a discourse of “games are legitimate, and not only are they legitimate, but they're more interesting than any of your artwork”!

I do think games have interesting, unique things to offer. But I also think my perspective, and the whole landscape, has softened over the years. These days I think about games as just one more medium. And regarding different media, I don’t necessarily think one is more interesting or superior than others. These are just distinct avenues for creativity.

But there’s something interesting in literature, painting, and music, for example, which are established art forms with long, historical pedigrees. You have this acceptance and understanding that these things are part of the human experience and reflect different aspects of that.

And then you have cinema, which I believe has kind of been the historic touchstone for games, since it was the newer medium. People looked suspiciously at it early on, and said it wasn’t really art. But eventually it became accepted, and nowadays you have movies that are considered cult classics, great works of art. So in the early 2000s, that historical reference was the big hope for games.

Every medium has its unique characteristics and things that make it interesting. And the aspect of interactivity, the agency, this is what I think makes people keep coming back to games. It is a different kind of experience.

I think it was Will Wright (The Sims, SimCity, Spore) who said that games have a different emotional palette in comparison to other media. He said, “I never felt pride, or guilt, watching a movie.” I think that’s still a useful observation. You might feel discomfort watching a movie, but it’s not you who is doing or going through something.

Quite simply, this is the thing with video games. It’s the only medium where people will describe something they experienced first person, right? You can watch or read something and it may impact you, but as Will Wright said, games have this distinct emotional impact.

With Loneliness, for example, it was such a tiny, simple, little game. Some people have said that it is so simple that it could have been an animation. It’s an interesting idea, but once in a while, I get emails from people who played it and they always say something about what they did in the game, and how the game reacted to it, and how they felt.

I guess that’s the unique thing about it. And I don’t think that makes games superior to any other medium, it’s just that it’s a fundamentally different experience. You have this recollection, this memory of something you did, something you encountered, like having gone through something, having experienced something yourself.

That’s powerful, because it’s closer to actual experiences in our lives. So that is the power of interactivity, of agency.

And that also makes you more present, right? You could put a movie on a screen, for example, and whoever’s watching… their eyes could be open, they could be staring at the screen, but their mind could be elsewhere. Like when you’re reading sometimes and not really paying attention, so you have to go back and read again.

But games usually force you to actually be more fully engaged on a continuous basis. Of course, there are games and specific situations where you don’t need to pay attention, just go by muscle memory. But for many games, and especially if you’re playing something for the first time, you can’t really advance without being fully engaged, because you have to interact with the game in order to move forward.

👻 I really like the Will Wright quote you mentioned. And yes, I feel like playing games is a more personal experience, especially in branching narratives. For example, if you’ve played Skyrim, fans will ask if you killed or spared Paarthurnax, the dragon, or if you decided to join the Imperials or the Stormcloaks.

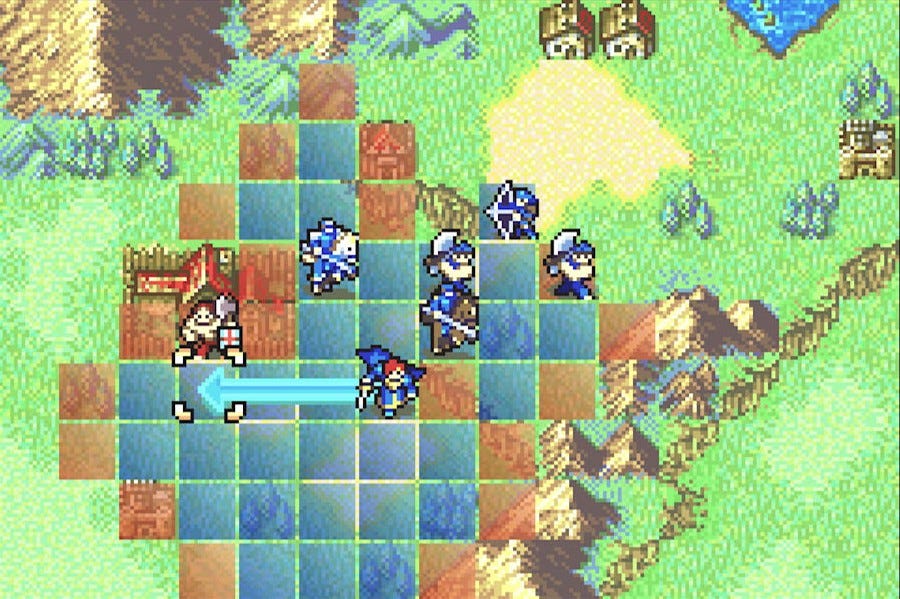

👻 Another good example is the Fire Emblem series. It’s a tactical fantasy RPG with some social simulation aspects. I was introduced to it by a friend and I played it while I was an undergrad student. Anyway, Fire Emblem has quite a deep lore and well-developed characters, you get deeply attached to them.

👻 But the game also has a permanent death feature, so if a character dies, they are really gone. Whenever I let a character die, I not only felt sad, but guilty, because that was a consequence of my actions. So I think that if someone just aced it, and no one died in their playthrough, their experience would have been wildly different.

Yeah, and with cinema, for example, if you go to a movie theatre, it is a shared experience. Everyone can feel differently about it, of course, but everyone is seeing the same thing.

But in some games, particularly the ones that feature different pathways, branching narratives and all, it’s remarkable how different people’s experiences of the same game can be.

So in these huge online games, like World of Warcraft, there are so many options, right? And of course, you see themes, trends and similarities, but you also see just a huge spectrum.

And this is something we still have a hard time with, coming from studies on more traditional media, because all of our tools for analysing or thinking about art and literature are very difficult to apply in that kind of context.

So for games, we have these different kinds of analysis happening, especially player experience and this kind of thing. So we are still asking ourselves, how do we make meaning out of these texts that operate very differently from most of the texts that we've analysed historically?

👻 Exactly, I do think games are vastly different in this sense. Although there have been experiences with branching narratives in other media in the past, it wasn’t as spread out.

👻 And this other thing you said about having to be engaged with the game. I think this ties back to something you said before: as kids, we just seem to have this infinite amount of time, and we keep playing. Maybe that was never about time, it was just about how present we were. And that may be the magic of video games, that they invite you to be mindful, right? They invite you to pay attention to what you’re doing.

This mindful connection in play intrigues me. I’ve seen a couple of people who have written about game playing and mindfulness, with a focus on meditation practice. It’s curious, right, because on the surface, playing a game and meditating are such different practices. Playing something is oftentimes fast-moving and frenetic, versus the slowing down that meditation brings.

Of course, I don’t want to casually equate the two things. They are vastly different, but there is something interesting in that possible connection.

I only get so much game playing time these days, but when I do play a game, one of the things I appreciate is this feeling of presence, of being fully focused. Because it’s so easy for me to have my mind going in too many directions on a hundred different things, which is very tiring.

Meditation really helps me with that, but then it’s also very intriguing that playing the right game can also help me focus my mind.

👻 And finally, I’d like to end with a few recommendations from you. What are some of your favourite games and poets?

I’ll just go from the top of my mind, because I am teaching a class at the moment on critical and experimental game design. One is “The Stuff Games Are Made Of” by Pippin Barr.

He's an experimental game maker, quite prolific and well-known within the world of experimental game making. He’s got this wonderful book, and he's been making experimental games for a long time, with a very consistent output.

In this book, he dives into his thoughts and approach to game design. It’s just phenomenal.

So Pippin Barr brings in that amazing thing about being an experimental game designer, this question of how do you toy with and push and pull games. And discusses all these little pieces that make up a game and how you might do something different.

You take a game like Pong, for example, and you make 50 variations of it. One of Pippin Barr’s games is just called Pongs. And he used the original Pong game, and its mechanics, to create a game about refugees instead of table tennis.

It’s a fantastic book for anyone interested in looking at games more critically, or from a more creative standpoint.

Another book I’m using in my class is Doris Rusch’s “Making Deep Games”. It is a book that considers how video games have been getting conceptually deeper and more diverse in themes and genres. It goes into approaches to make deep, complex games.

So this resonates for me due to its connection to poetry as well, these deep themes that are historically connected to poetry. And how we can dive in and make games about these sorts of things. It’s a book based on her own experience, experimentation, and trial-and-errors over the years.

“Twining: Critical and Creative Approaches to Hypertext Narratives” is the other book I use in this class. It’s one I really like, and it’s open access, which is great. It goes into the hypertext tradition, and discusses Twine projects.

So Twine is an open-source tool to create hypertext and interactive fiction works. It became massively popular around 10 years ago. You didn’t need the background or technical interest in game design to get into it: if you were interested in interactivity and narrative, you could just use this very accessible tool to make little interactive text-based games.

This book is a really nice exploration and also sort of a little how-to manual that provides a critical approach to interactive narrative and hypertext.

With games, it’s even harder, I don’t even know where to start! Books are already hard, but because I’m teaching a class, I have these go-to books that I’m using. Games are more of a coin toss. So I’ll just go with games that I’ve played recently and kind of stuck with me.

Venba (2023) is one of them. It’s a short, two-hour game. It is a game about an immigrant family experience told through cooking game mechanics. It’s fantastic, really original. The reason it stood out to me is simply because it’s well-done all the way through. It is exactly the type of game I would like to see more of.

It is designed to be a two to three hour play experience, and I think this is a super wonderful time frame. Especially these days, with the limited time I have, this is a perfect length.

And the original thing about it is that it is a narrative cooking game, right? Many cooking games are about technique, understanding and mastering mechanics. But this one delivers a narrative through cooking. And that was so fresh, and a sweet short experience.

Oh, Spiritfarer (2020) was another amazing, artful game that I’ve recently played. It is a bittersweet, also relatively short game about death.

You can read the “Game Poems” book for free, and check out Jordan’s games here! He’s also got a curated collection of game poems.

— The ghost murmuring poems at your ear in the dead of night,

almoghost.exe (or André Almo if you’re feeling serious) 👻

"You take a game like Pong, for example, and you make 50 variations of it. One of Pippin Barr’s games is just called Pongs. And he used the original Pong game, and its mechanics, to create a game about refugees instead of table tennis."

this snippet of the interview is mind blowing. i never played the game, but i feel like the original Pong mechanics is used as a... metaphor?

I thought I would reading a text about putting a layer of poetry over the gaming stuff, and the poetry would be something metalinguistical. I mean, like Guitar Hero is not a musical game, but a game based in music that already existed. or like The Last of Us, that also gamefied playing chords on an acoustic guitar... This is not about gamifying poetry, it is something deeper!

Game mechanics can have the same logic and affection properties in the same way that poetry or music do! if one is able to create a metonymy, or an euphemism, even irony only with a set of game mechanics structures, it could create a game poem!

It's crazy, the backend developer, looking into the terminals and writing the chunks of codes would become the artist itself! MINDBLOWING

Thanks for the lovely read. So many ideas to get lost in. But especially timely for personal reasons is that of not-game. To break the bounds which contains it. Applies to everything.