It was 2002, and my teenage cousin Liz had forgotten her Tamagotchi at my grandma’s house. She had left for a 1-week trip to a neighbouring coastal town, and, while in a rush to pack and leave, abandoned her digital companion.

When she realised she wasn't carrying the device, she panicked and called our grandmother. After listening to detailed instructions over the phone, my grandma assured her she’d care for her Tamagotchi.

And, of course, my grandma had no intention of babysitting a beeping plastic egg. My cousin’s Tamagotchi didn’t last much — starving, neglected, and ultimately abandoned to the digital void.

My cousin wasn't alone in the virtual pet craze. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a wave of games, anime, and digital experiences emerged, each presenting unique digital creatures and worlds.

Tamagotchi, Digimon, Mega Man Battle Network and Telefang are four examples of franchises with a common theme: digital realms inhabited by digital beings, but somehow connected to the physical world and its physical residents.

These fictional digital companions could learn, evolve, and even form emotional bonds with their human partners. Let’s sync up with these digital worlds and decode the links that unite them!

Tamagotchi: hatching the digital egg

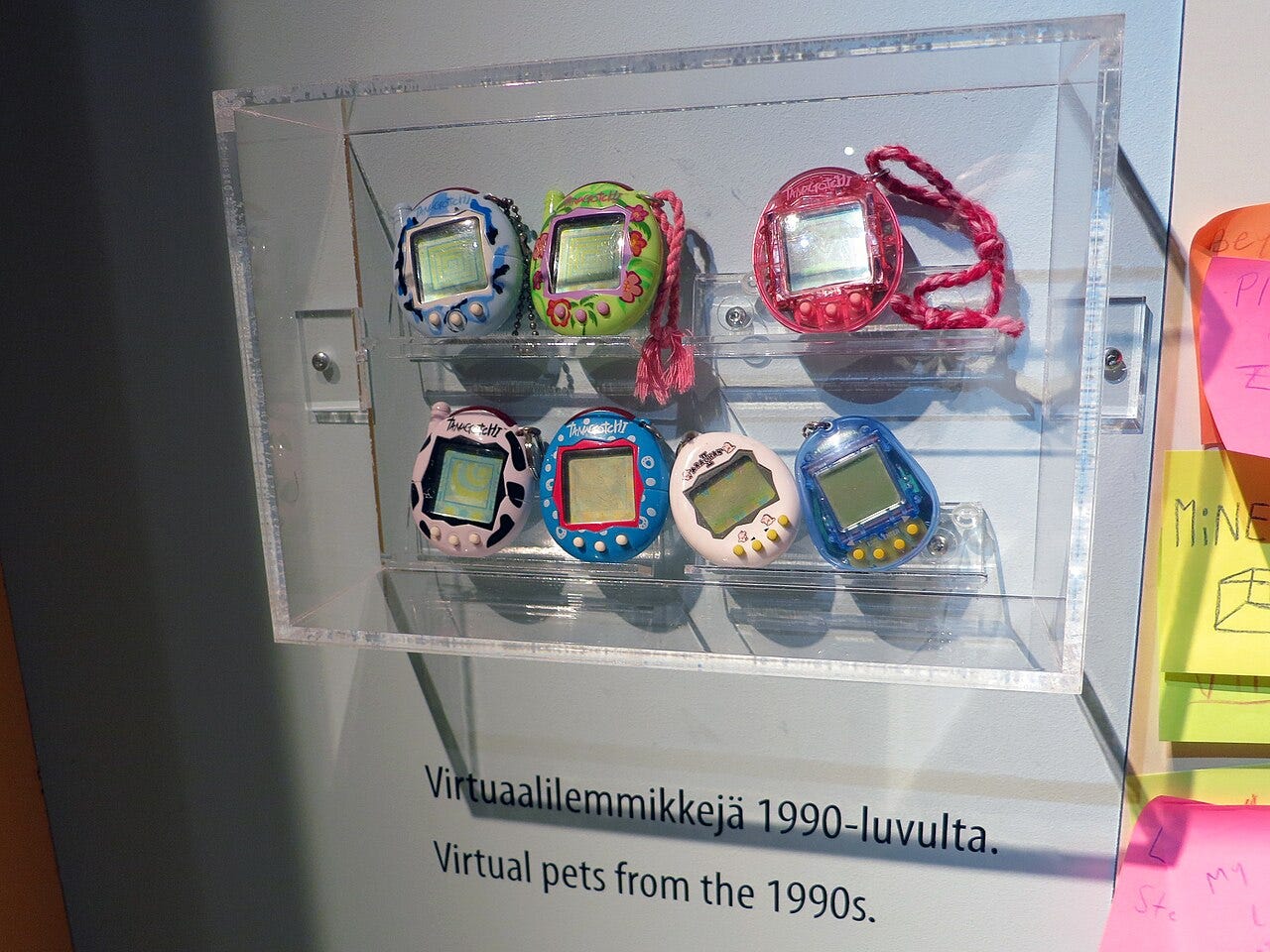

The Tamagotchi was created in Japan by Akihiro Yokoi (from Bandai) and Aki Maita (from WiZ). Released by Bandai in 1996, this tiny egg-shaped device let players nurture a digital creature, feeding it, cleaning up after it, and making sure it didn’t meet an untimely demise.

This was the original virtual pet phenomenon, a sweeping toy craze that won over kids and teens across both the East and the West.

While there were certainly other “digital pet” precursors — such as the Petz franchise — the Tamagotchi stood out for being played in a dedicated handheld device, rather than a computer or video game console, and for featuring its own fictional creatures rather than simply simulating real-world animals.

According to the game’s short and straightforward lore, Tamagotchi creatures were small, harmless extraterrestrials who had come to Earth. Players took on the role of their caretakers, raising them from eggs into fully grown adults — who still managed to look cute.

Despite its simple mechanics, Tamagotchi introduced a fundamental concept: a digital being dependent on real-world interaction for its survival and growth.

Tamagotchi wasn’t just a game — it was an experiment in digital responsibility. The creatures lived in their own minimalistic world inside the device, yet their needs dictated real-life actions. This concept of real-world influence over a digital entity — and vice-versa — became a defining trait in many franchises that followed.

And just like the creatures inside it, the Tamagotchi itself has evolved. Over the years, the franchise has expanded through multiple generations of devices, each introducing more complex mechanics and features.

Later models allowed players to connect their Tamagotchi to others, unlocking social interactions, careers, and even family life. The addition of colour screens, more customisation options, and infrared or Bluetooth connectivity gave the creatures more depth and expressiveness than ever before.

Today, Tamagotchi lives on in both dedicated handheld consoles and mobile apps, blending its nostalgic appeal with modern technology. Whether in a pocket-sized device or a smartphone screen, its core identity remains unchanged: a digital companion that asks for care, attention, and, inevitably, just a little bit of love.

Tamagotchi wasn’t just a passing fad — as evidenced by the many models the brand has launched —, although one could say the toy had peaked in the 1990s. However, the product’s global sales doubled between 2022 and 2023, and the brand now has a store in the United Kingdom. Maybe the Tamagotchi fever never passed after all.

And if you still haven’t gotten the Tamagotchi bug, beware! Their partnerships with other franchises keep multiplying, and one of these days, it might very well find its way to something you like.

Digimon: Virtual Pets That Fight and Evolve

While Tamagotchi attracts diverse audiences, Bandai had initially marketed the product towards young girls; among whom the toy was more popular in Japan. In an effort to expand into the masculine market, Bandai and WiZ created an alternative Tamagotchi in 1997: the Digital Monster (or Digimon).

Thus, Digimon was born as a Tamagotchi spin-off that took the virtual pet concept and added battles, evolution, and a deeper lore. Unlike the Tamagotchi, the Digimon weren’t simply creatures to nurture; they could fight, protect their partners, and grow stronger.

Digimon has evolved into one of the most ambitious explorations of digital companionship in media. What began as a battling pet concept soon expanded into a sprawling sci-fi narrative across anime, video games, and films, transforming Digimon into something far more complex — intelligent beings born of data, living in a parallel digital universe capable of influencing our own.

As the franchise grew, so did its themes, blurring the line between human and digital life. Digimon were more than just creatures to collect; they were friends, allies, and reflections of the people who raised them — inviting players and viewers alike to imagine a world where data could think, feel, and form bonds.

Digimon in TV: Digital Partners, Digital Worlds

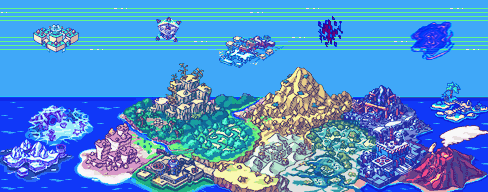

Digimon Adventure debuted in 1999, depicting the Digimon as sentient beings living in an expansive Digital World — a parallel dimension made of data, influenced by human networks and technology.

The Digivice, a small handheld device carried by each of the show’s main characters (the DigiDestined), was the key to this connection. It acted as both a partner link and a power source, enabling Digimon to evolve (or, more specifically, to Digivolve) into stronger forms when needed.

The Digital World wasn’t just a simple parallel dimension or a battleground, but rather a place filled with distinct societies, ancient legends, and real stakes. This interplay of a digital existence tied to the human world became a defining trait of the franchise.

In 2001, Digimon Tamers took the concept in a new direction, blending its virtual creatures even deeper into the real world. Unlike its predecessors, Tamers wasn’t about kids being chosen to save a separate digital realm. Instead, it was set in a realistic Tokyo, where Digimon were initially nothing more than a trading card game.

But what if these creatures were real?

In this version of the mythos, Digimon were autonomous AI programmes, organically emerging from the vast sea of human data. When they broke into the real world, they weren’t bound by fate or prophecy — they were wild, existing outside of human control.

Unlike the DigiDestined before them, the Tamers had to manually train and strengthen their Digimon, using Battle Cards to provide stat boosts and abilities. Additionally, when their Digimon defeated an opponent, they could absorb their data, growing stronger.

This gave Digimon Tamers a darker, more philosophical tone, exploring themes of artificial intelligence, autonomy, government surveillance, and the blurred line between human and digital life.

With the rise of smartphones, App Monsters (2016) took Digimon into the app age. Instead of purely existing in a separate Digital World, the Appmon were creatures born from applications — AI-based lifeforms linked directly to the devices we use every day.

The concept leaned further into AI ethics, questioning what happens when digital beings become too intelligent or independent.

The series thus touches on the hypothetical idea of technological singularity — a point in time where technological progress becomes irreversible and uncontrollable, with automated intelligent agents entering a cycle of self-perpetuated development.

Their intelligence would greatly surpass our own, leading to unforeseen consequences. With recent advancements in generative AI and its surge in popularity through chatbots like ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Deepseek, and Grok, these themes are more timely than ever.

Digimon games: Digital Worlds You Can Step Into

This evolving mythology was mirrored in Digimon’s games, which evolved from simple virtual pets into complete digital worlds.

The first Digimon devices, released in 1997, were essentially battle-focused Tamagotchi. Players could feed, train, and care for their Digimon, who could battle other digital creatures.

Over time, Bandai released more advanced Digimon pets, introducing multiple alternative evolutionary paths based on training — a digital companion you could truly shape.

More recently, the Vital Bracelet combined Digimon evolution with fitness tracking, making real-world exercise a factor in a Digimon’s growth. This brought the creatures’ digital world and our physical one much closer, as both the Digimon and its human partner needed to train in order to evolve.

Digimon also found a strong foothold on consoles; as the franchise expanded into video games, it continued to deepen its central mythos: the idea that the Digital World is not just a setting, but a living system shaped by human connection.

Across different titles, players aren’t merely trainers — they’re caretakers, moral compasses, and digital architects. Series like Digimon World brought this to life by linking a Digimon’s evolution — and to some extent, the Digital World itself — to the player’s actions, care, and discipline, suggesting that human behaviour could sculpt digital life.

Later titles merged these pet-raising mechanics with traditional RPG elements, enabling deeper exploration of the Digital World’s geography, its factions, and its ancient data-driven lore.

In the Digimon Story series, beginning in 2006 in the Nintendo DS, the Digital World became even more integrated with our own, evolving into a mirror for real-world technologies and issues. Digimon could be scanned, digitised, or even hacked — their forms were again not fixed, but malleable, able to evolve or regress along branching paths depending on player choices.

Two more recent titles, Digimon Story: Cyber Sleuth (2015) and Digimon Story: Hacker’s Memory (2017), featured hackers using Digimon as tools in an underground digital war. These games particularly delved into themes of data privacy, AI autonomy, and hacking ethics — all wrapped in a mystery-driven narrative.

In 2022, Digimon Survive turned the Digital World into a space of moral weight. Digimon’s evolution paths were directly tied to the protagonist’s personality and decisions, reinforcing the idea that these creatures are more than data — they are shaped by empathy, belief, and fear. Death, loss, and transformation were no longer abstract game mechanics but part of the emotional fabric of the story.

Across all these games, one message remains clear: the Digital World is not static. It’s alive, responsive, and fundamentally intertwined with the human spirit. Whether through data, care, or conscience, our presence changes it — and it, in turn, reflects who we are.

Mega Man Battle Network: The Internet as a Living World

Where Digimon often imagines the Digital World as a parallel dimension — one that intersects with ours but retains its own ecosystem — Mega Man Battle Network (Rockman.EXE in Japan) further collapses that boundary.

Released by Capcom in 2001 for the Game Boy Advance, this series reimagined Mega Man as an AI programme, or NetNavi, living inside a handheld PET (Personal Terminal) device.

Over the course of six main entries, The Mega Man Battle Network games refined its unique blend of real-time strategy, deck-building, and RPG mechanics, with each installment introducing new features, storylines, and an evolving cyberspace.

Set in a highly digitalised future, Battle Network introduced a world where almost everything — from household appliances to public infrastructure — was connected to the internet. This concept closely resembles what we now call the Internet of Things (IoT): a network of smart devices that communicate with each other and automate daily tasks.

In Battle Network, this hyper-connected world meant that fridges, traffic lights, ovens, and even school blackboards had their own digital systems, which could be accessed, modified, or even hacked through a cyberspace, called Cybernet.

People interacted with this digital ecosystem through NetNavis, personal AI assistants that helped them navigate the cyberspace, manage information, and even battle rogue programs. The PET devices and NetNavis functioned as personal IoT managers, showcasing both the potential and risks of a fully networked society.

Jacking In

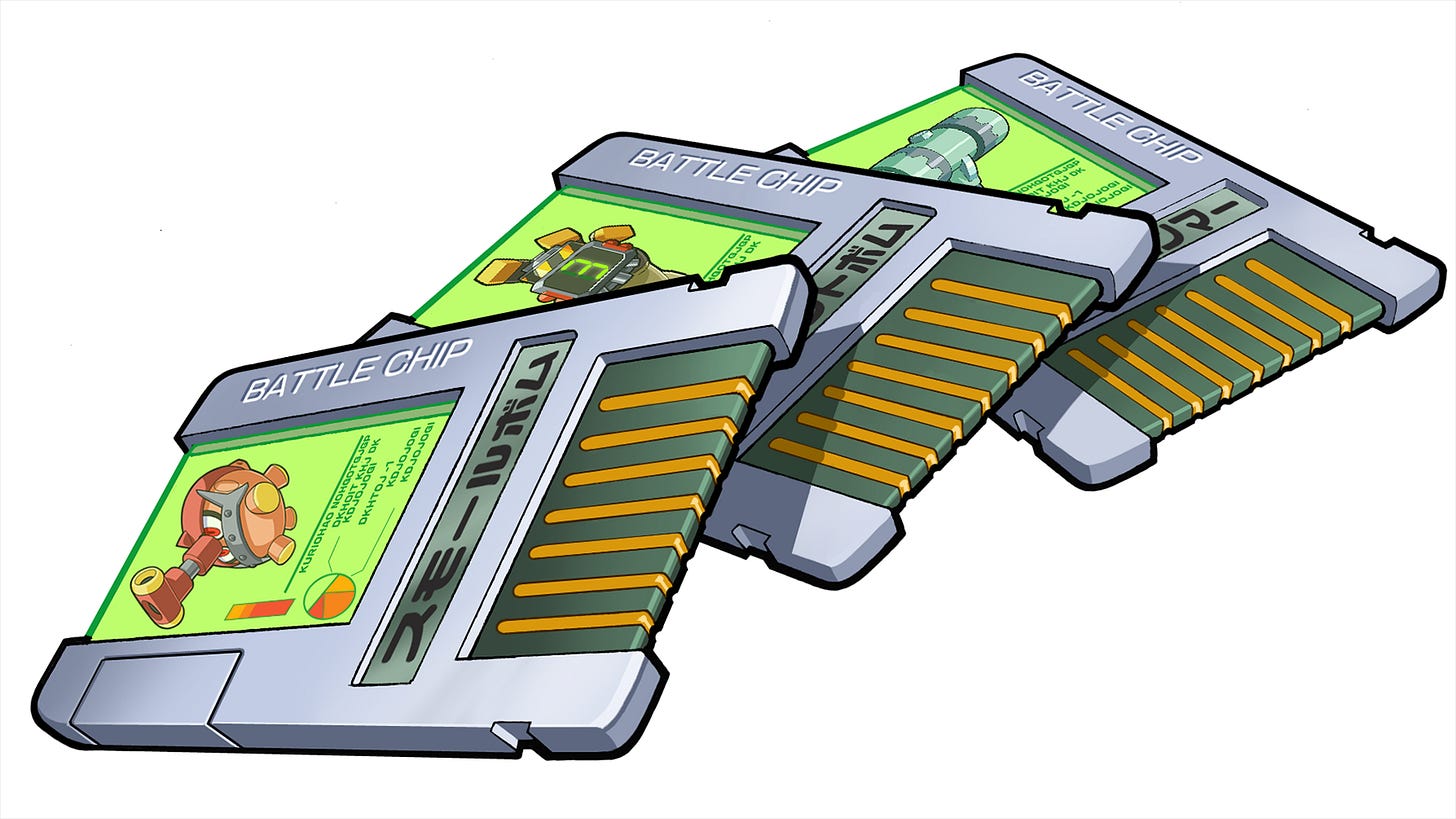

One of the defining mechanics of Battle Network was the ability to "jack in" — sending your NetNavi into the digital world to explore, battle viruses, and interact with other programmes.

This mirrored real-world online interactions: viruses acted as rogue malware, firewalls had to be bypassed, and cyber battles resembled hacking duels.

The games also introduced the unique "chip system", where players could upload Battle Chips in real time to execute powerful attacks, making combat feel dynamic and strategic.

NetNavis: More Than Just Tools

Thematically, Battle Network posed an interesting question: what if our digital assistants were more than just tools? Unlike simple software, NetNavis had personalities, emotions, and even friendships with their human Operators. This was the heart of the series — players weren’t just controlling a character; they were forming a bond with their NetNavi.

The relationship between protagonist Lan Hikari and his NetNavi, MegaMan.EXE, was central to the story. Over the course of the series, they fought cybercriminals, uncovered conspiracies, and explored the blurred line between AI companionship and human relationships.

Beyond the Game Boy: Anime, PET Devices, and Legacy

The popularity of Battle Network led to a long-running anime adaptation, MegaMan NT Warrior, which expanded on the world and characters. The anime portrayed the internet as a vast digital metropolis, where NetNavis coexisted in a structured society, facing cybercriminals, rogue AIs, and evolving digital threats.

Beyond traditional video games, Battle Network also had a real-world tie-in with the PET (Personal Terminal) devices, interactive handheld toys that simulated the experience of owning a NetNavi.

These PET toys allowed players to train their digital companions, battle others via link cable, and even slot in physical battle chips — mirroring the mechanics seen in the anime and games. This further cemented Battle Network as a unique fusion of RPG and virtual pet gameplay.

Today, Battle Network remains a cult favourite, inspiring discussions about AI ethics, digital relationships, and the evolving role of the internet in our lives. The 2023 Battle Network Legacy Collection reintroduced the series to a modern audience, proving that its vision of a living, breathing internet is more relevant than ever.

Telefang: A Digital World Overlooked

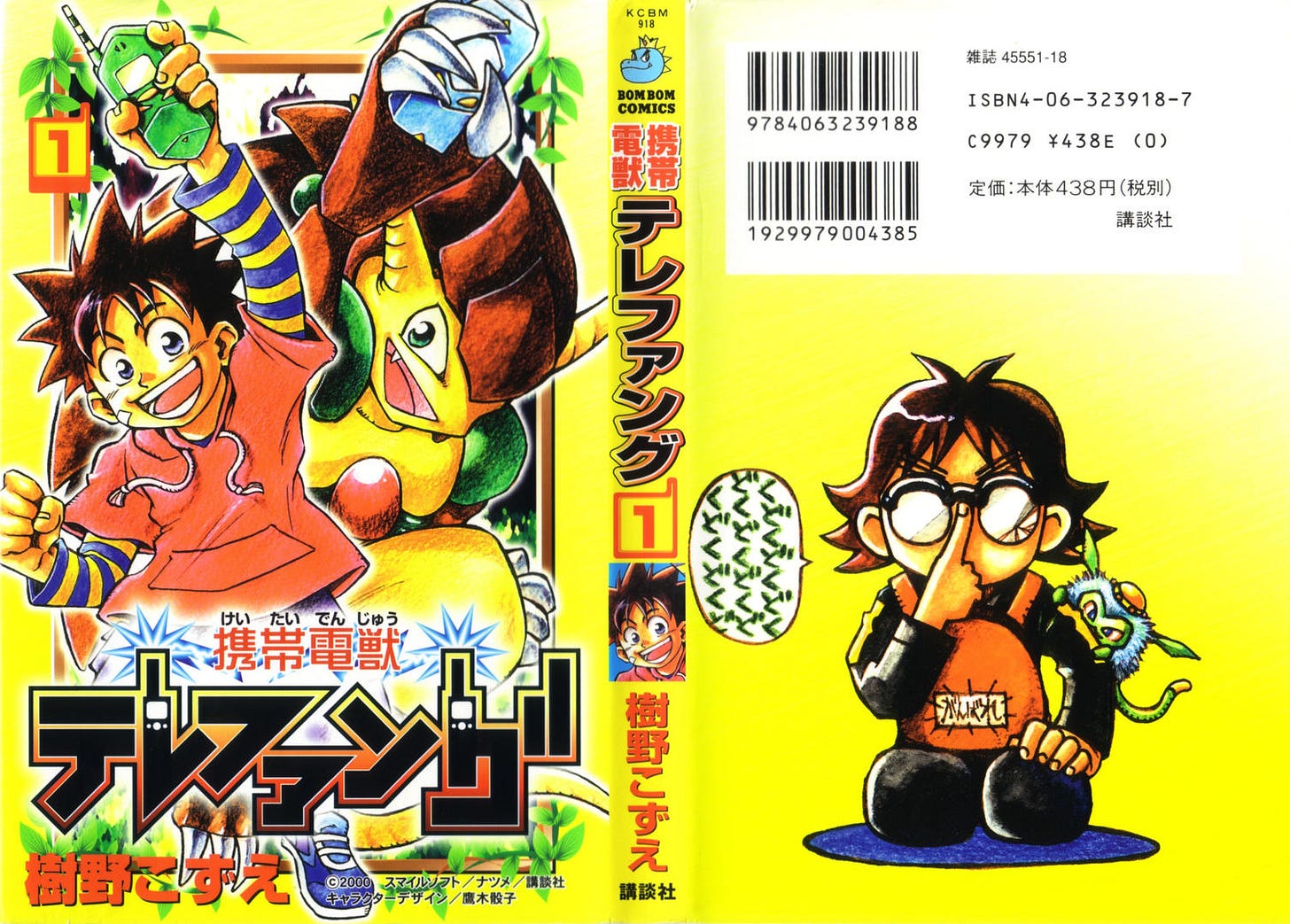

Among these franchises, Keitai Denjū Telefang remains the most obscure, yet it shares key thematic similarities. Released in 2000 for the Game Boy Color, Telefang introduced a world where creatures, called Denjū, communicated with humans via mobile phones.

Instead of capturing them like Pokémon, players had to dial their numbers in-game, convincing them to form bonds and answer their calls for battle.

This unique mechanic set Telefang apart, making its creatures feel more like independent digital beings rather than collectibles. Some Denjū would ignore repeated calls, while others would only respond at specific times, simulating real-world phone interactions and adding a layer of unpredictability.

The game’s world functioned more like a networked ecosystem, where Denjū had their own lives and relationships rather than simply existing for human trainers.

Despite its innovative premise, Telefang never saw widespread success, largely due to its limited release in Japan. However, its influence lingers.

The idea of using phones as a gateway to a hidden digital world was ahead of its time, foreshadowing mobile gaming trends where players interact with digital creatures via apps. Additionally, its depiction of Denjū as self-governing beings with their own motivations aligns with the deeper AI and digital autonomy themes seen in Digimon and Battle Network.

Connecting franchises

Each of these franchises presents digital beings in different ways, but there are similarities — they are entities with their own ecosystems, rules, and relationships that redefine how players interact with digital worlds.

They exist within distinct digital realms, whether inside a dedicated device (Tamagotchi), a parallel universe with its own history and conflicts (Digimon), an intricately interconnected cyberspace (both Battle Network and Digimon), or a communication-based world within mobile networks (Telefang). Each of these settings treats digital life as something tangible and structured, rather than a mere abstraction.

These digital beings require real-world interaction, often demanding attention, care, and decision-making from humans.

A Tamagotchi would wither if neglected. Digimon and NetNavis depended on training choices, emotional bonds, and battles. In Telefang, Denjū weren’t simply caught — they had to be convinced to answer a call and might refuse based on time, luck, or relationship level. These mechanics blurred the line between game and reality, making the player feel personally responsible for their digital companion.

These franchises explore the idea of companionship with digital lifeforms, challenging players to reconsider what it means to form a bond with something artificial yet emotionally responsive.

The bond between Digimon Adventure's DigiDestined and their partners often resembled friendship rather than ownership, while Battle Network’s Lan and MegaMan.EXE had a sibling-like relationship, deeply intertwined with the game’s narrative.

Even in the simplest interactions — like a Tamagotchi needing care or a Denjū deciding whether to answer a call — these games encouraged emotional investment.

These themes feel even more relevant today. Machine Learning allows programmes to adapt and "learn" from their users. AI companions and chatbots can hold conversations with increasing complexity. Virtual influencers are growing in popularity. Some modern, more sophisticated virtual pets can recognise faces and voices.

As technology continues to evolve, the once-fictional dream of meaningful relationships with digital beings isn’t so far from reality; Tamagotchi, Digimon, Battle Network, and Telefang no longer feel like mere fantasy — they feel like a glimpse into what may come.

— The digital ghost companion,

almoghost.exe (or André Almo if you’re feeling serious) 👻

This text made me feel like I really underestimated digimon… it isn’t worse than Pokémon at all!

What a great read! Was hardcore stressed by the opening anecdote about a tamagotchi left behind. That would’ve been the worst thing ever.